Connective tissue forms a significant and vitally important component of nearly every organ. As we study the human body organ system by organ system, it is easy to forget the importance of connective tissue simply because it is ubiquitous and serves universal functions, rather than being special with novel functions. Never let this bland familiarity cause you to lose sight of the existence and significance of ordinary connective tissue. Inflammation is a principal function for connective tissue and the blood vessels which pass through it.

LOCATION of connective tissue

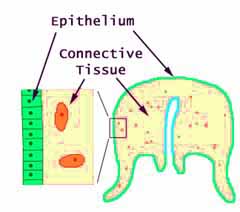

The location of connective tissue relative to other tissues may be easily understood in a simple animal like a jellyfish.

Most of the bulk of a jellyfish is a mass of jelly (yellow, in figure at right), which is the animal's connective tissue. A thin epithelium (green) covers the outside, and an internal digestive cavity is also lined by a thin epithelium (blue).

The connective tissue matrix (the jelly itself, pale yellow in the figure) is manufactured by scattered cells (orange) embedded within it.

The connective-tissue jelly supports the epithelium and permits free diffusion of nutrients and metabolites. These two functions of mechanical and nutritional support are basic to all connective tissues. To these two major functions may also be added a third, immunological protection.

This simple arrangement of tissues also characterizes early embryos. An external layer of epithelial tissue (ectoderm) and an internal layer of epithelial tissue (endoderm) are separated from one another by a space filled with mesenchyme, the name given to embryonic connective tissue.

Most adult connective tissue is derived from mesenchyme. Thus, the locations where connective tissue is found in the adult are analogous to the location of mesenchyme in the embryo -- in between ectoderm and endoderm.

Blood vessels and muscle tissue are also derived from mesenchyme, so that blood vessels and muscles are always embedded within connective tissue.

Nerves grow out into connective tissue from the neuroectodermally derived central nervous system, so nerves are also embedded in connective tissue.

As a result of this basic topology, other tissues are either supported upon connective tissue (epithelial surfaces), invaginated into connective tissue (glandular epithelium), or embedded within the connective tissue (blood vessels, muscles, and nerves).

Our internal epithelial surfaces are much more complex than those of the jellyfish. Epithelial surfaces line the nasal and oral passages; the digestive, respiratory, reproductive and urinary tracts; and even the ducts and secretory portions of various glands (e.g., liver, pancreas, kidneys). Neverthless, as in the jellyfish, the basic tissue arrangement in all of these organs includes connective tissue supporting a layer of epithelial cells.

Organs (i.e., organized combinations of the four basic tissue types) are composed of parenchyma supported by stroma. The stroma is the connective tissue and the associated blood vessels and nerves which pass through it. The stroma supports the parenchyma, which in turn consists of those epithelial, muscle, or nerve cells which carry out the specific function(s) of the organ and which usually comprise the bulk of the organ.

Examples of connective tissue location:

COMPONENTS of Connective Tissue

Connective tissue consists of cells embedded in an extracellular matrix. The matrix, in turn, consists of fibers and ground substance.

Fibroblasts are the most common resident cells in ordinary connective tissue. These are the cells responsible for secreting collagen and other elements of the extracellular matrix. In so doing, fibroblasts are essential for normal development and repair.

Throughout the body, fibroblasts all appear similar to one another. The nuclei of resting fibroblasts appear dense (heterochromatic) and are usually flattened or spindle-shaped. Resting fibroblasts typically have so little cytoplasm that the cells commonly appear, by light microscopy, as "naked" nuclei. (In the thumbnail image at right, the pink material is extracellular collagen.)

In microscopic appearance, even by electron microscopy, fibroblasts lack obvious specialized features. "Nondescript" is perhaps the best word to describe the appearance of these cells in routine histological specimens. There is little about fibroblasts to attract the attention of a casual observer. Indeed, fibroblasts "are frequently overlooked as 'merely' ubiquitous supportive cells," to quote from a 2015 report in the journal Science (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aab0120).

However, significantly, each fibroblast knows where in the body it resides and how it should contribute appropriately to the body's various connective tissues. As reported in PLoS (28 July 2006), individual fibroblasts express the genetic equivalent of a ZIP code: "Fibroblasts from different anatomic sites have distinct and characteristic gene expression patterns" which are "systematically related to their positional identities relative to major anatomic axes. For example, a cell on the hand expresses a set of genes that locate the cell on the top half of the body (anterior) and another set of genes that locates the cell as being far away from the body or distal and a third set of genes that identifies the cell on the outside of the body (not internal)."

This specificity of location is evident not only in the mechanical differences among various examples of loose and dense connective tissues, such as tendon, ligament, and fascia, but most notably in the transparency of the cornea of the eye.

Indeed, the single cell type called "fibroblast" may properly represent many distinctly (but invisibly) different cell types, such as "tendinocytes" (fibroblasts of tendons), "keratocytes" (fibroblasts of cornea), and "fasciacytes" (fibroblasts of fascia, so named in some texts, e.g., here). Undifferentiated "mesenchymal stem cells," which retain a capacity for differentiation into other cell types (see Science 324:1666, 26 June 2009) may also be found within populations of fibroblasts.

For the role of fibroblasts in penile erection, see Science 383 (9 Feb 2024), DOI: 10.1126/science.ade8064.

The name "fibroblast" itself is something of a misnomer, since most cells with "blast" in their name are embryonic precursor cells which subsequently differentiate into specialized cell types. Fibroblasts, though, are already a mature, differentiated cell type (although some may retain the capacity to differentiate into other mesenchymal cell types as well).

Fibroblasts are normally quiescent in mature tissues but become activated during tissue repair following injury. (Fibroblasts may also become activated during adaptive responses to mechanical stresses.) When active, fibroblasts are manufacturing and secreting collagen and other components of extracellular matrix at the site of growth or tissue damage. Active fibroblasts appear larger than resting ones, with more cytoplasm and with nuclei that are more euchromatic (less densely stained); some texts refer to active fibroblasts as fibrocytes.

Scar formation: Resting fibroblasts retain the ability to become active and to multiply when necessary, as during healing after injury. Scars are formed by fibroblast activity during tissue repair. The substance of the scar is collagen deposited by fibroblasts to replace damaged tissue.

For an image of scar formation, see WebPath.

For recent research on fibroblast involvement in scar formation, see Science (17 April 2015) and Science (23 April 2021).

Closely related to fibroblasts are the chondroblasts which produce the matrix of cartilage and the osteoblasts which produce the matrix of bone.

Terminology: The appearance of "blast" in a cell name normally indicates an embryonic cell that transforms into a mature cell type (e.g., neuroblast, myoblast). However, in the case of "fibroblast," "chondroblast," and "osteoblast," this designation indicates a cell which secretes fibers, cartilage or bone.

TOP OF PAGE

Adipocytes. Adipocytes are large connective tissue cells which contain a substantial amount of lipid stored in the form of conspicuous round droplets. Adipocytes function primarily as warehouses for reserve energy. They also have endocrine function, secreting the hormone leptin to regulate hunger. En masse hypodermal adipocytes can also assist in thermoregulation (maintaining body temperature) by providing some insulation. In a few sites adipocytes also offer some cushioning capacity (e.g., around kidneys, behind eyeballs).

Since most loose connective tissue contains scattered clusters of adipocytes, the term adipose tissue is usually reserved for large masses (grossly visible) of these cells.

The most common type of adipocyte is called the unilocular adipocyte or white fat. Each cell contains one single fat droplet (hence, unilocular) surrounded by a thin rim of cytoplasm.

Under the light microscope, the appearance of an adipocyte is that of a conspicuous clear space with a very thin border. The lipid droplet which comprises the bulk of each adipocytes is not stained by ordinary aqueous stains, and may even be removed by solvents during specimen preparation. Furthermore, adipocyte cytoplasm itself is inconspicuously thin, and the nucleus of any particular adipocyte is unlikely to be included in any given section (see Viewing Tissues).

On microscope slides, clusters of adipocytes present an appearance somewhat like a "foam." The individual "bubbles," each representing a lipid droplet within a single cell, are fairly consistent in size. Typical fat cell diameter is about 50 micrometers, comparable to a skeletal muscle fiber or a small (terminal) arteriole.

The shape of the droplet, in a tissue section on a slide, depends on how carefully the specimen was prepared. Ideally the droplets are smooth and round (as in the image above), but they may also be distorted, shaped more like jigsaw-puzzle pieces (as in the image at right).

Adipocytes may occur in almost any sample of ordinary connective tissue, where they may be found as individual cells or in clumps. Even when clustered together and apparently touching, adipocytes remain separated by a thin layer of matrix (ground substance and collagen) which includes numerous capillaries.

A layer of adipose tissue in the deep layers of skin (variously called hypodermis or subcutaneous adipose) may provide significant thermal insulation.

A more specialized and localized type of adipocyte is called the multilocular adipocyte or brown fat. These cells function in thermogeneration, essentially burning fat to produce heat.

Individual brown fat cells contain numerous small lipid droplets (hence the name multilocular) and numerous mitochondria (whose cytochromes confer a brownish color to unstained brown fat). In these cells, the metabolic reactions of the mitochondria are uncoupled from ATP synthesis so that energy produced is simply released as heat.

Infants have a substantial amount of brown fat, especially in a pad between the shoulder blades. Brown fat is scarce in adults but may be found around the adrenal gland. Recent research (three articles in New England Journal of Medicine 360[15], 9 April 2009) reported brown fat in a region extending from the anterior neck to the thorax; brown fat activity was positively related to resting metabolic rate and was significantly lower in overweight or obese subjects than in lean subjects.

TOP OF PAGE

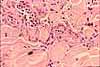

Macrophages remove and digest the by-products of both bacterial warfare and normal growth and degeneration. Resting macrophages are difficult to recognize reliably by light microscopy, at least in routine preparations, because they lack conspicuous distinguishing characteristics. They tend to be somewhat larger than fibroblasts, with more cytoplasm. Macrophages contain numerous lysosomes which are used for breaking down ingested material. These lysosomes are usually inconspicuous by light microscopy but readily visible by electron microscopy.

In macrophages which have been active and have accumulated indigestible residue, the lysosomes may be visible by light microscopy as brown intracellular granules, as in this image of lung macrophages ("dust cells"). Click here or on the image for a wider-field view and more information on lung macrophages.

Historical notes: Macrophages of liver (Kupffer cells) and of lung (dust cells) were named prior to clear understanding that these cells belong to a more widely distributed cell type.

The obsolete term reticuloendothelial system refers to the macrophages of the liver, spleen and lymph nodes (i.e., those organs with elaborate endothelially-lined channels supported by reticular connective tissue). The name reflects former confusion about the distinction between endothelial cells and the scattered population of macrophages (monocytes, histiocytes). Macrophages can be readily labelled experimentally through their phagocytosis of injected carbon particles. However, endothelial cells are also labelled by the same procedure. Although endothelial cells are not dramatically phagocytotic, they do shuttle some materials across the endothelial lining via small endocytotic and exocytotic vesicles.

Macrophages are mobile (amoeboid movement) over short distances within a local region of connective tissue. Most ordinary connective tissue contains a standing population of resident macrophages. But when damage or infection requires reinforcements, monocytes can increase the macrophage population many-fold. Monocytes are circulating cells in the blood which can differentiate into macrophages when they enter connective tissue.

Macrophages are among the most independent cells in the body. Although they respond to the chemical signals which govern immune responses, individual macrophages are capable of crawling out of connective tissue, crossing the body's epithelium, and scavenging foreign material on exposed surfaces such as the alveolar lining of the lung and the conjunctiva of the eye.

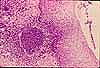

Macrophages attempt to engulf foreign material by gathering together and merging into foreign body giant cells (see Webpath). Those associated with granulomas (Webpath) are called Langhans giant cells ( commemorating Theodor Langhans, b. 1839 ).

TOP OF PAGE

Mast cells are secretory alarm cells. Upon the slightest disturbance, they release chemical signals which diffuse through the surrounding ground substance and trigger the process of inflammation.

Mast cells occur as small individual cells, scattered rather widely in ordinary connective tissue. The cytoplasm of mast cells is packed with secretory vesicles, which can be fairly conspicuous in high-quality light microscope preparations. The granules contain histamine, heparin, and various other chemical mediators whose release signals a number of physiological defense responses.

Allergies are caused (in part) by inappropriate sensitivity of mast cells. The symptoms are treated with antihistamines, chemicals which interfere with the action of histamine.

Historical note. The name "mast cell" is a misnomer. The word "mast" refers to food. When first described, the secretory vesicles of mast cells were misinterpreted as evidence of ingestion by phagocytosis. So the name suggests a cell which has eaten its fill of "mast."

Lymphocytes are principal elements of the immune system. They are small cells with round nuclei and minimal cytoplasm (the example shown here is from a blood smear). Some lymphocytes circulate throughout the body, moving freely from blood to ordinary connective tissue and back again. [Recent research suggests that some types of lymphocytes are more compartmentalized.] Lymphocytes serve both as scouts and as weapons against invading microorganisms.

Lymphocytes occur as inconspicuous individual cells scattered through most ordinary connective tissues. They are especially common in lamina propria (i.e., the connective tissues of mucous membranes). Microscopically conspicuous accumulations of lymphocytes occur in scattered sites around the body, with special concentrations in spleen, thymus, lymph nodes, Peyer's patches of ileum, and tonsils. These sites include germinal centers where activated lymphocytes proliferate.

Lymphocytes manufacture antibodies, proteins which possess the ability to recognize and bind to foreign substances. The antibodies may be either secreted or bound to the lymphocyte membrane. Plasma cells are differentiated lymphocytes which are specialized to manufacture and secrete relatively large amounts of antibody.

Other connective tissue cell types. The list above is not exhaustive.

EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX

The extracellular matrix of connective tissue is composed of fibers and ground substance. In ordinary connective tissue, the principal fiber type is collagen (the most abundant protein in the body), with elastic fibers as a minor element; ground substance consists mainly of water.

This matrix is considerably more complex than described below. For a readable review of this complexity, including its interactions with associated cells, see Science vol. 369, p. 659 (2023).

Ground substance is the background material within which all other connective tissue elements are embedded. In ordinary connective tissue, the ground substance consists mainly of water whose major role is to provide a route for communication and transport (by diffusion) between tissues. This water is stabilized by a complex of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), proteoglycans, and glycoproteins, all of which comprise only a small fraction of the weight of the ground substance.

The effect of GAGs in water is quite like that of Jello. If you've ever made Jello, you know that a couple tablespoons of powder from the Jello package can turn a quart or more of water from a flowing liquid into a solid mass.

Ground substance may be highly modified in the special forms of connective tissue.

The extracellular fibers of connective tissue are traditionally classified into three types:

Collagen is the most common protein in the body. As an essential structural element in the extracellular matrix of most connective tissues, including bone and cartilage, collagen confers toughness and tensile strength. Scars are made of collagen.

More than a dozen different varieties of collagen exist in the body, usually identified by Roman numerals. These varieties are produced by different genes, have somewhat different properties, and occur in different locations. The most common forms are listed below.

The type I collagen fibers of ordinary fibrous connective tissue are colorless, so in most cases their bulk appearance is white (e.g., the "white" of the eye and other organ sheaths, of tendons, and of fascia). Whiteness results from scattering of light (the same reason that snow is white, even though snowflakes are transparent crystalline ice). Under extraordinary circumstances of regular fiber arrangement and controlled extracellular fluid, as in the cornea of the eye, bulk collagen can be transparent.

Although colorless, type I collagen is eosinophilic and so appears pink in routine H&E stained tissue specimens. Such pink collagen fibers are the most prominent feature of ordinary connective tissue. The ability to locate and identify connective tissue on slides is largely the ability to recognize collagen fibers. (Collagen can be selectively stained with trichrome stains, to help distinguish it from other eosinophilic fibers like smooth muscle.)

Collagen is produced by fibroblasts.

Fibroblasts secrete procollagen molecules, which are converted extracellularly into tropocollagen. Tropocollagen then self-assembles into microscopically visible fibers and grossly evident mechanical structures such as tendons. (For further introduction to the biochemistry and related pathology of collagen synthesis, see Kierszenbaum, Histology and Cell Biology, or follow this link to the NIH NLM.)

The assembly of collagen into anatomical features seems almost magical, since the process takes place in extracellular space, presumably guided (somehow) by fibroblasts. This "magic" is perhaps most evident in the cornea of the eye. In routine histological preparations, the cornea is almost indistiguishable from the sclera. Both consist of densely-packed collagen fibers. But whereas the sclera (the "white" of the eye) is opaque, the cornea is marvellously transparent. In the cornea, collagen fibers are arranged into an almost crystalline array of extremely regular layers, with fiber orientation parallel within each layer but alternating between adjacent layers. (Activity of corneal endothelial cells is also essential to maintain the appropriate fluid balance for transparency

Elastin is another fibrous protein. As the name suggests, elastin is elastic. In ordinary connective tissue, elastic fibers help restore normal shape after distortion. In high enough concentrations, elastin confers a yellowish color (as in the elastic ligament, ligamentum flavum, where flavum = yellow)

Like rubber bands, elastic fibers can deteriorate with age and exposure to sun. This effect is easily demonstrated by recruiting two volunteers, one youthful and one elderly. Pinch up a bit of skin on the back of each person's hand and then watch how quickly the skin returns to its original position when released.

In elastic ligaments, dense elastic fiber concentrations convey strong elastic properties while a lesser concentration of collagen serves simply as a mechanical stop to prevent over-stretching under severe stress.

In addition to its occurrence as a minor constituent in most ordinary connective tissue, elastin is also characteristic of arterial walls (especially elastic arteries such as the aorta) and of elastic cartilage (found in ear and epiglottis).

Elastic fibers are often poorly stained by H&E, and so are seen microscopically only with specially stained slides.

"Special" connective tissue. Within a background texture of rather universally distributed ordinary connective tissue, there also occur several very highly differentiated and localized forms of "special" connective tissue, which nevertheless share many common features (structural components, cell lineages) with connective tissue proper. These special forms include bone, cartilage, lymphoid tissue (spleen and lymph nodes), blood, and bone marrow.

In routine use, the term "connective tissue" usually refers to ordinary connective tissue, while the special forms are more commonly referred to by their specific names (e.g., bone, cartilage, blood).

TOP OF PAGE

Loose / Dense. Connective tissue may be distinguished as either loose or dense, depending on the proportion of fibers. The intrinsic strength of collagen is the same in both loose and dense connective tissue.

Loose and dense are not two different kinds of connective tissue, but rather descriptors for a continuous range of variation in looseness / denseness.

The difference between moderately loose connective tissue and moderately dense connective tissue is difficult to appreciate by microscopy, since inadvertent compression or stretching may reduce or exaggerate the space between the fibers. This difference is better appreciated at the level of gross anatomy.

If a fresh sample of loose connective were hit with a hammer, it would "squish." If a sample of really dense connective tissue, such as tendon, were hit, the hammer would bounce back.

But there is no sharp distinction between loose and dense connective tissue; the labels refer to the extremes of a continuum.

Dense connective tissue is so named because of high density of extracellular fibers, and relatively smaller proportions of ground substance and cells.

Densely packed type I collagen fibers provide main strength with resistance to tearing and stretching.

Dense collagenous connective tissue is found wherever the tensile strength of collagen is of paramount importance. Examples include dermis (the layer of the skin which yields leather), tendons and ligaments, and organ sheaths (such as the "white" of the eye (sclera), the cornea, or the capsule of the kidney).

Dense elastic connective tissue is found wherever the elasticity of elastin is of paramount importance, as in the ligamentum flavum (flavum refers to the yellow color conferred by the elastin) and the aorta.

Loose connective tissue has a relatively large proportion of ground substance, of cells, or of both cells and ground substance. In other words, loose connective tissue lacks the massive fibrous reinforcement that characterizes dense connective tissue. Nevertheless, the same types of fibers are still found, although fewer and more delicate.

Fluid may be able to move fairly freely through loose connective tissue. Bruising ("ecchymosis") can display evidence of such movement.

Loose connective tissue is easily distorted, permitting tissues on either side to move freely with respect to one another. However, when loose connective tissue is distorted sufficiently, it too becomes tough and resists further deformation.

Loosely packed collagen fibers (in tissues such as hypodermis or the submucosa of internal organs) allow free movement within definite limits.

Do-it-yourself demonstration: To experience the mechanical quality of loose connective tissue, try the following. (1) Pinch the skin of one cheek between thumb and forefinger. (2) Hold the lining (mucosa) of that cheek between your teeth. (3) Then move the skin relative to the lining. See how far the two surfaces can move relative to one another. The freedom is due to the looseness of the intervening connective tissue. The limits are set by the collagen fibers which become straightened until taut.

Ordinary loose connective tissue, sometimes called areolar tissue, is common throughout the body. (The word areolar refers to areolar tissue's variable spaces (areolae) filled with ground substance.) Examples of areolar tissue include hypodermis, lamina propria, submucosa, mesentery, and fascia. (Fascia [L., band] is the term used in gross anatomy for the connective tissue that loosely binds together various other structures.)

Regular/Irregular. Dense connective tissue may be further described as either regular or irregular, depending on the orientation of the fibers.

In regular connective tissue (example: tendon) the fibers are all aligned in a single direction, conferring tensile strength primarily in that direction.

In irregular connective tissue (example: dermis) the fibers are arranged in various directions, although even here collagen fibers may adopt a preferential orientation as revealed by "Langer's lines."

Fibrocollagenous (or just fibrous) tissue contains a substantial proportion of collagen. A principal feature of fibrous tissue is flexibility combined with great tensile strength.

Because collagen is colorless and typically scatters light, fibrous connective tissue usually appears white.

The sclera (or "white") of the eye is a readily visible example of dense fibrous connective tissue comprising an organ sheath.

Tendons and muscle capsules may also be familiar from the butcher shop or anatomy lab. The ends of muscle fibers are typically attached to dense fibrous connective tissue of periosteum, tendon, or ligament.

The dermis of the skin is also fibrous connective tissue (hence, leather is mostly collagen).

Elastic tissue is a dense connective tissue which contains predominantly elastic fibers rather than collagen. It is more elastic (obviously) than dense collagenous connective tissue.

Examples include the wall of the aorta and the elastic ligament of the spine (called ligamentum flavum [flavum = yellow] because in sufficient quantity elastin is yellowish).

Adipose tissue is loose connective tissue which is dominated by fat cells, or adipocytes. Since most loose connective tissue contains scattered clusters of adipocytes, the term adipose tissue is usually reserved for large masses (grossly visible) of these cells.

Lymphoid tissue is loose connective tissue with large numbers of lymphocytes that have accumulated in the tissue. Lamina propria (the loose connective tissue of mucosal surfaces) often shows lymphatic tendencies, or even fairly well-developed lymph nodules. The immune cells in these locations form a vital second line of defense (the epithelium with its continuous but rather easily broken wall was the first line) against invading microorganisms.

A separate page describes the lymphatic system, including lymphoid tissues in several specialized lymphoid organs -- spleen, thymus, lymph nodes, and tonsils. Lymphoid organs are also sometimes called reticular tissue because of the supporting framework of reticular fibers (a delicate, branching form of collagen).

Areolar tissue is another name for loose irregular connective tissue, with unspecialized proportions of the various matrix components and cells. The word "areolar" in its name refers to the many small spaces (areolae), of variable size and filled with ground substance, that characterize this tissue. Examples of areolar tissue occur throughout the body.

Historical note: Among the 21 simple tissues described by Bichat in 1801, areolar tissue occupies first place (Bichat's 1° tissu le cellulaire). Bichat recognized the significance of areolar tissue in the spread and/or limitation of inflammatory processes.

For a fascinating essay on the "discovery" of areolar tissue, see Forrester: "The homoeomerous parts and their replacement by Bichat's tissues," in Medical History, 1994, 38: 444-458, especially pp. 452-454.

Although areolar tissue may be seen on many slides, slide sets commonly include a whole-mount preparation of mesentery which is labelled as "Areolar Tissue."

Blood is traditionally classified as a specialized form of connective tissue, with no fibers, highly fluid ground substance, and mobile cells. Blood is thus distinct from ordinary connective tissue. However, blood may also be usefully regarded as simply a fraction of ordinary connective tissue that is free to gallop around from place to place along differentiated highways. (Follow the links for a more extensive discussion of blood.)

Only the red blood cells, like trolley cars, are confined to the highways (i.e., blood vessels). All other cell types in blood, and most plasma constituents as well, can circulate rather freely from blood to connective tissue and back again. Thus, most of the mobile cellular components of ordinary connective tissue are interchangeable with those in blood.

Cell names may differ between blood and ordinary connective tissue. The cells which are called macrophages in ordinary connective tissue are called monocytes in blood. Blood cells similar to tissue mast cells are called basophils. From this point of view, the term "white blood cell" is not only very nonspecific but is also a misnomer. "Circulating connective tissue cell" (still nonspecific) better fits the functional location of these mobile cell types.

Bone and cartilage are special forms of connective tissue, made by specialized osteoblasts and chondroblasts, with uniquely solidified ground substance. These forms are described on a separate page, as skeletal tissue.

The circulatory system is the familiar mechanism for moving materials around the body. However, blood vessels do not go quite far enough. Most cells are not situated directly against capillaries, but rather some tens or even hundreds of micrometers (several cell diameters) away from the nearest blood vessel.

Connective tissue (more specifically the stabilized water in the ground substance) provides the final pathway for diffusion of nutrients, oxygen, waste and metabolites to and from the cells of the body.

Subcutaneous and intramuscular injection of drugs also makes use of connective tissue as the initial transport medium.

All blood vessels are embedded in connective tissue. The only cells which receive their sustenance directly from the blood are the endothelial cells lining the vessels themselves. All other cells are supplied via diffusion through intermediary connective tissue.

The transport functions of blood and connective tissue cannot be separated. In essence, blood is really just a mobile fraction of connective tissue. The heart and circulatory system simply facilitate the movement of this traveling tissue.

Whenever you find elaborate capillary beds closely associated with groups of cells (such as the capillary networks enveloping skeletal muscle fibers or encircling secretory acini), you can predict that these cells must have some exceptionally high demand for transport in or out, since a resting cell can live quite happily at some distance from the nearest blood supply. Rich capillary supply is characteristic of muscle and brain (supplying oxygen), lung (acquiring oxygen), intestinal villi (collecting nutrients), exocrine glands (delivering raw materials for secretion), and endocrine glands (collecting hormones).

Immunological surveillance and defense

Connective tissue serves not only as a transportation route for the body's normal economy but also as a convenient route for invading microorganisms. To provide defense against this eventuality, an army of various cell types is deployed throughout the connective tissue.

Ordinary connective tissue includes two resident cell types with immunological function, mast cells and macrophages. (Resident cells, which essentially remain fixed in place waiting for action, are distinguished from wandering or immigrant cells which migrate in and out of the tissue.)

Mast cells are secretory alarm cells. They are very fragile, rupturing at any disturbance. The release of their granules (stored secretory product) triggers a number of physiological defense mechanisms, including inflammation.

Macrophages remove and digest the by-products of both bacterial warfare and normal growth and degeneration. Monocytes, which are circulating cells in the blood, differentiate into macrophages when they enter connective tissue. Macrophages are mobile (amoeboid movement) over short distances within a local region of connective tissue. But when an invasion requires reinforcements, immigrating monocytes can increase the macrophage population many-fold.

Other fixed cells (i.e., fibroblasts and fat cells) are primarily structural, although fibroblast activity (cell proliferation and secretion of collagen) is an important aspect of the healing process.

Ordinary connective tissue also includes several wandering cell types, also called white blood cells, which travel in and out of connective tissue. Five basic types may be considered (follow the links for each cell type, for much more detail):

The distribution of the wandering immune cells reflects ongoing physiological and pathological processes.

For more about the immune system, see CRR Lymphatic System.

Mechanical Support

The mechanical quality of most ordinary connective tissue is affected only indirectly by the cells which occur within it (unlike epithelial tissue, which consists entirely of cells).

An exception is adipose tissue, where the sheer bulk of many adipocytes can offer mechanical protection by cushioning impact.

The major determinant of the mechanical properties of most connective tissue is the extracellular matrix which is secreted by the cells within it (fibroblasts in ordinary connective tissue, osteoblasts and chondroblasts in bone and cartilage respectively).

In ordinary connective tissue, the ground substance is too fluid to provide much strength. The jelly-like ground substance of ordinary connective tissue serves mainly to prevent extracellular water from pooling in the lowest part of your body. But ground substance can be a major structural feature in special forms such as cartilage and bone.

In most connective tissue, extracellular fibers form the main structural elements.

Collagen offers flexibility with high tensile strength. Densely packed collagen fibers provide strength with resistance to tearing and stretching. Loosely packed collagen fibers allow free movement within definite limits.

Reticular fibers (really, a special form of collagen) provide a delicate supporting framework for individual cells, especially when such cells accumulate en masse to form a large solid organ such as the spleen or the liver.

Elastin, as the name suggests, is stretchy like rubber bands, helping restore normal shape after distortion. In elastic ligaments and arteries dense elastic fiber concentrations convey strong elastic properties while a lesser concentration of collagen serves simply as a mechanical stop to prevent over-stretching under severe stress.

Growth and Repair. The most common fixed cell of ordinary connective tissue proper is the fibroblast. Fibroblasts are normally quiescent in the adult. During growth and also during repair after injury fibroblasts are active secretory cells which manufacture the fibers and ground substance of connective tissue. They also retain the ability to multiply when necessary, as during wound healing, and possibly to differentiate into other mesenchymally derived cell types (such as vascular endothelium and smooth muscle). Myofibroblasts resemble fibroblasts but have an additional contractile ability, useful for example for closing wounds.

A scar is collagen deposited by fibroblasts during repair.

According to recent research, genetically differentiated fibroblasts may also be responsible for guiding localized patterns of tissue organization during growth and repair.

Energy Economics. Connective tissue is involved in several interrelated ways with energy storage and thermoregulation.

The burden of reserve energy storage falls almost entirely on adipocytes.

Many other cells, especially muscle cells, have short-term energy stores in the form of intracellular glycogen. A larger, but still comparatively small, energy reserve is also provided by glycogen in hepatocytes (the epithelial cells of liver). But adipocytes exceed all other cell types for calories stored per cell.

Accumulations of subcutaneous fat cells also provide thermal insulation. And specialized brown fat (also called multilocular fat) is responsible for generating heat to maintain body temperature under circumstances when insulation is not sufficient. This heat-producing function is especially significant for infants (and other small mammals) and may be related to metabolic rate in adult humans.

Haemopoiesis, the process of blood cell formation, also falls to connective tissue. In the adult, haemopoiesis takes place in the connective tissue of bone marrow. Bone marrow is specialized for this role. (Pass over this lightly now. You should learn more in Year Two.)